Cate Blanchett’s “queer icon status” brings a metatextual layer to her role as Lydia Tár.

Blanchett became a bonified “lesbian icon” and the subject of countless lesbian meme pages after her infamous role in the lesbian period drama Carol (2015). A film where Blanchett plays a middle-aged 1950s housewife romancing a younger shopgirl.

Carol became somewhat of an internet sensation that amassed a fanbase of digital dykes who produced fan edits of the film, compiled interview clips of Cate Blanchett and co-star Rooney Mara, ran Tumblr pages, and circulated glove GIF sets. In an interview with the programmer of New York’s Metrograph Theater, Aliza Ma told WIRED that “people have joked that Carol is our Eraserhead because we keep showing it and it keeps selling out and it’s just this weird cult that’s developed here”.

Blanchett's growing lesbian fanbase only became more apparent when she played Lou Miller, a queer-coded con artist in Ocean’s 8 (2018). This film, alongside the assortment of pantsuits Blanchett wore during its press tour, birthed the Instagram page @dykeblanchett. An account solely dedicated to Blanchett's “sapphic looks” and queer-related memes that amassed over 50,000 followers.

During the 2023 Tár press junket, Blanchett’s so-called “sapphic success” became the subject of interviews. When asked about her status as a “lesbian icon” in an interview with Attitude Magazine, Blanchett replied, “I don’t know what it means, but I’ll take it”. Nonetheless, the combination of Blacnhett’s queer (or subtextually queer) role choices and publicity strategies in recent years has brought into question whether the actress is perhaps cultivating or “leaning into” this newfound “queer icon status”

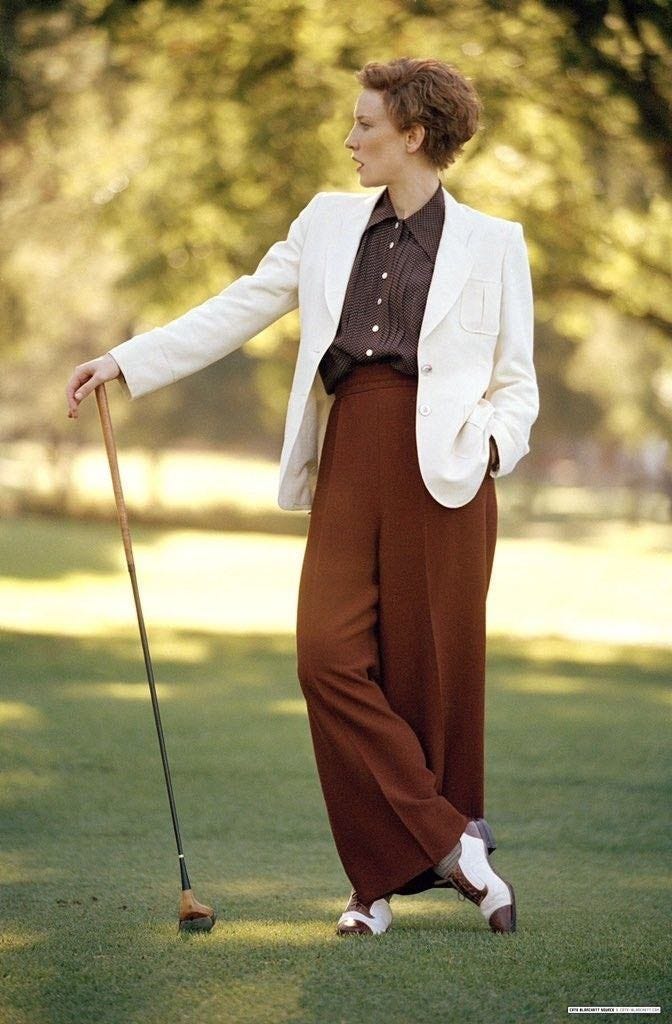

Lesbian cult stars are no new phenomenon and can be traced back to the Hollywood star system of the 1920s and 30s. These “dykons” accumulated lesbian cult followings not for their explicit imagings or openly out identities, but for the queer cultural readings of their work (Kabir 2016, 3). In films like Queen Christina (1933), and Slyvia Scarlett (1935), gender inversion and “mannish butch” stereotypes were embraced and, even seen as liberating images for some lesbians (Weiss 1992, 40). Despite the negative connotations of these “inversions” onscreen, lesbian spectators revised and redefined such pathologies in ways that centred on pleasure rather than perversions (1992, 163). Naturally, many of the early female stars who embodied this androgyny; namely Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich and Louise Brooks were lusted over by lesbian spectators who also sought to emulate their styles of dress.

Pictured: Greta Garbo in Queen Christina (1933)

Engineered as a star vehicle for Blanchett, comparisons can be drawn between Tár and the lesbian cult statuses that George Cukor and Dorothy Arzner’s star vehicles carved out for Greta Garbo and Katherine Hepburn (who Blanchett happened to play in The Aviator (2003)). Whilst Blanchett has been dubbed the “Garbo of the digital age” for her lesbian-inflected iconography, Garbo was by all accounts a queer woman, whereas Blanchett (at least publically) is not. Despite this, Blanchett has been a staunch defender of “straight actors playing gay”, a discourse that opens up its own can of worms.

Regardless of the star’s off-screen sexuality, Michael DeAngelis argues in his book Gay Fandom and Crossover Stardom that the sexual ambivalence of star personas (like Blanchett’s) enable both straight and gay spectators to access these personas through star texts and discourses that operate as fantasy (2001, 5). Across her lesbian iconography, Blanchett moves between “femme” (Carol) and “butch” (Ocean’s 8 and Tár) identifications with ease. Her turn as Bob Dylan in Todd Hayne’s I’m Not There (2007) and the 13 distinctive personas she adopted in Manifesto (2015) are also exemplary of the star’s ambiguity-an ambiguity that Blanchett has said to have channelled into her role in Tár.

Tár is a film that operates on a metatextual level.1

The maestro’s doting fans and female protégées feel undeniably meta when Blanchett’s “lesbian icon” status is taken into account. Not to mention the fact that Tár nods to the queer canon by casting Blanchett opposite Portrait of a Lady on Fire’s (2019) Noémie Merlant.

The film does not hesitate to establish millennial women’s enamorment with the maestro. Within the first 10 minutes of the film, a female admirer (who “casually” mentions she’s a Smith College alumna) flirts with Tár, who returns the favour by praising her Hermes Birkin Bag. Tár later tells her wife that the same Birkin was a gift from fellow conductor Elliot, a lie shrouded in ambiguity as to whether Tár slept with her admirer or accepted the bag as a token of her admiration. As the scene unfolds, Tár’s assistant Francesca (played by Merlant) watches the encounter from the sidelines and rolls her eyes in exasperation, privy to the knowledge that this exchange has happened before.

When I first watched Tár command a room, there was an undeniable sense of elation in seeing a masculine lesbian with “poise” and prowess being actively desired by other women on screen. However, as the narrative progressed, the “dangerous masculinity”, that had made Tár so alluring in the first place, left me conflicted when her transgressions came to light.

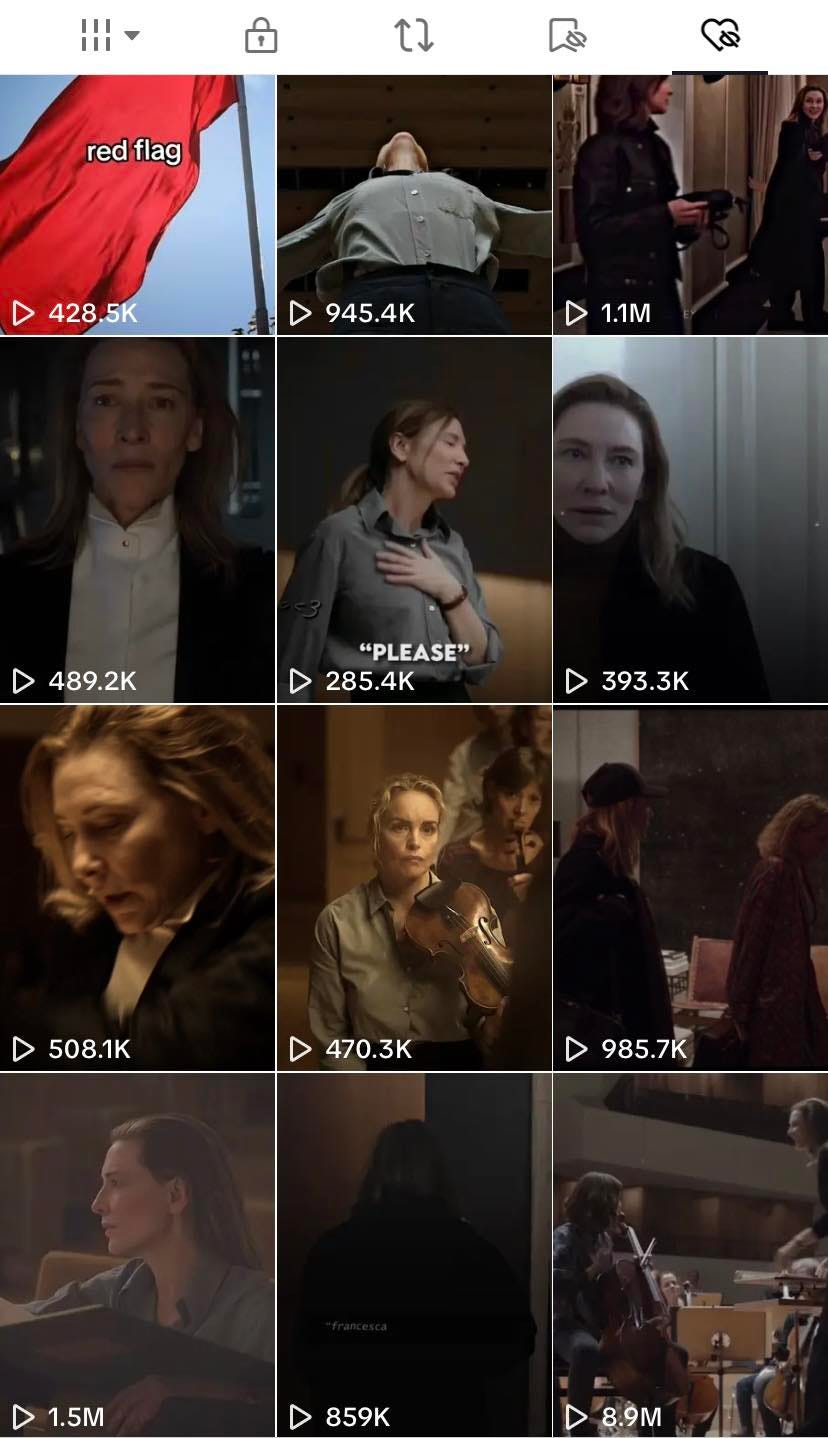

Following Tár’s release in late 2022, an onslaught of fan edits circulated on TikTok and Twitter. Combined, these videos amassed millions of views across platforms with comments sections flooded by queer women swooning over Cate Blanchett as Lydia Tár. One TikTok with 8.9 million views paired a fan cam edit of Tár and her newest victim, Olga to Melanie Martinez’s Teacher’s Pet (a song about predation and inappropriate teacher-student relations). The top comments written under the video by girls, reading “I would die if someone did that to me”, “my mommy issues are screaming rn” and, “she’s daddy”.

In a titular scene that inspired hundreds of “Cate Blanchett mommy/daddy” reviews on Letterboxd, Tár refers to herself as “Petra’s father” when threatening her daughter’s school bully. Ironically, it is the scenes that evoke queer spectatorial pleasure that simultaneously reveal how Tár wielded her power to abuse her victims.

What is it about the character of Lydia Tár (or Cate Blanchett in a fitted suit) that taps into a perverse configuration of dyke desire shared by so many queer women online?

By looking at how Cate Blanchett’s star persona and “dykon” status have shaped the internet’s allurement towards Tár’s lesbian anti-hero, Todd Field’s film about power, abuse and celebrity becomes unequivocally meta or meTá(r) if you will.

Reference List

DeAngelis, Michael. 2001. Gay Fandom and Crossover Stardom : James Dean, Mel Gibson, and Keanu Reeves. Duke University Press. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=16a63ae1-c65e-3162-8c1d-202e16208c1a.

Kabir, Shameem. 2016. Daughters of Desire : Lesbian Representations in Film / Shameem Kabir. Bloomsbury Academic. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=8ea0df59-7e9c-3f36-8ab0-a9fb5aa29d89.

Weiss, Andrea. 1992. Vampires & Violets : Lesbians in the Cinema / Andrea Weiss. Cape. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=1284dc3c-3d9b-3bd6-8968-e93fb57512bb.

metatextuality is defined as a text that makes critical commentary on itself.